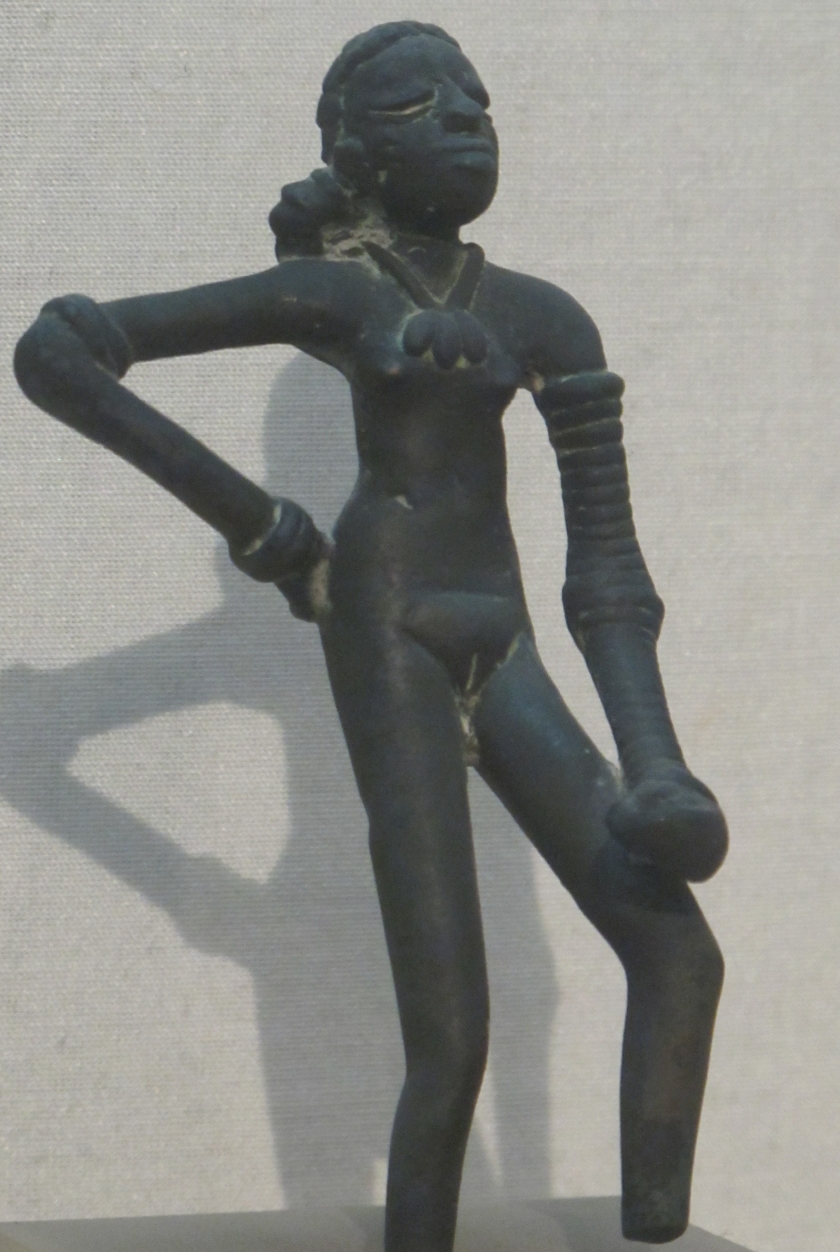

‘There is little Baluchi-style face with pouting lips and insolent look in the eye. She’s about 15 years old I should think, not mere, but she stand there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl perfectly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There is nothing like her, I think, in the world.’

Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Archaeologist

1926 was one of the most remarkable years in Indian archaeology. An outstanding discovery made this year was the image of a dancing girl from a house in the 4500-year-old Bronze Age city of Mohenjo-Daro; a 10.8 cm high bronze statue sculpted using the lost wax method. It was the most favourite statuette of British archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler.

4,500 years later if the Mohenjo-Daro artisan, the creator of the dancing girl would have a chance to visit Odisha, he would undoubtedly feel at home. Even at the high-tech information age, he would have recognized the lost wax technique that he himself would have used in his time.

The Lost Wax technique, Cire Perdue in French is one of the oldest and most advanced crafts traced back the Bronze Age civilizations of Indus Valley, Egypt, Mesopotamia, China and later Greece and Aztec.

In India today the Cire Perdue makers, called Dhokra artisans are settled over a vast tract in Central and Eastern India, close to the mineral belt. However, in Odisha, they belong to the category of scheduled castes and only a couple of decades before they were nomadic wanderers making and supplying ritual objects, such as lamp stands to various rural households.

The process of making dhokra objects in Odisha has not much changed from the time of Bronze Age Civilization. Concentrated in two regions in Rayagada district of Southern Odisha amidst the mountains of the Eastern Ghats and in Sadeibareni in Dhenkanal, close to Bhubaneswar, the state capital, the Dhokra artisans of Odisha have been practising lost wax technique from time immemorial, even though it is difficult to say about the origin of the craft in the absence of primary sources. However, the discovery of a major hoard of bronze statues representing Buddhist and Jain divinities (7th-8th centuries CE) at Achuytrajpur near Chilika Lake suggests that Dhokra craft flourished in Odisha during Early Medieval Period producing high-quality objects for religious patronage. The hoard included 92 icons, most of which are of Buddhist affiliation, female figures, stupas and Jain Tirthankaras.

Travel Tips

Sadeibareni is a small village in Dhenkanal District of Odisha at a distance of 65 km from Bhubaneswar. You can either reach through Athagarh and Saptasajya Forest outer corridor or via Cuttack and Dhenkanal. Remember there is no signage for Sadeiberani. On Saptasajya – Dhenkanal Road that connects both Athagarh and Dhenkanal, you have to reach Bhapur Village first and then ask for Sadeiberani Village which is about 1 km from Bhapur.

There are no staying and food options at Sadeiberani. For accommodation, one can try at Dhenkanal, but for better options is Bhubaneswar or Cuttack are obvious choices. For a vintage heritage experience, you can try at Dhenkanal Palace (http://www.dhenkanalpalace.com/). They will arrange your trips to Saderiberani, besides scenic Saptasajya and Joranda, the centre of mystic Mahima Cult. While at Dhenkanal also visit Kapilash Hill well-known for its Shiva Temple and dense forest, a major elephant corridor. For a gastronomic experience try Dhenkanal Bara, the local version of more established South Indian Medu Vada while at Dhenkanal in any roadside eateries.

For dokra villages in Rayagada District (Jhingidi and Jagdalpur), Rayagada (50 km away) has the best-staying options. While at Jhingdi also plan for Naiyamagiri Hills, the abode of Dongoria Kondhs, especially on Wednesday morning when the weekly tribal market is held at Chatikona, on the foothills.

There are six steps involved in Dhokra craft making:

- Core making – a clay core is made, slightly smaller than the final object. The core may be hardened by finishing or sun drying.

- Modelling – a detailed wax module is built up around the core to the thickness of metal.

- Moulding – The wax model is coated with a thin layer of very fine clay, which will form an impression of every detail of the model. When this layer is dry and hard, further layers of clay are added to the mould. One or more pouring channels are provided, through which molten metal can fill the mould.

- De-waxing – The mould is preheated to melt the wax, and the molten wax poured out (it may be recovered for subsequent reuse). This leaves a cavity which has the exact size, shape and surface counters of the intending object.

- Casting – Molten metal is poured into the cavity and the mould left to cool.

- Finishing – The object is broken out of the mould. Traces of baked clay are removed and surface blemishes and defects repaired.

The daily life of Dhokra artisans in Odisha revolves around the processes mentioned above. The entire family works as a production unit. They work hard from dawn to dusk, but in monsoon, they find it difficult due to the moisture content in the air, which does not allow fast drying. Socially they live as an extended family. They believe in Lord Shiva and celebrate all Shaivite festivals, including Sankranti. Women do the most difficult task. Apart from their household jobs they also go to the forest to fetch firewood and also soil that is required for dhokra casting. Men mostly spend time in making the craft and the hard task of finishing the moulds and polishing after de-moulding.

The basic raw material for dhokra is brass, which is procured in the form of used brass utensils or any other brass scrap. The scraps are available locally from traders. Black soil or the chikita mati is the mud or soil procured from open fields.

Paddy husks or kundaa obtained from mills are mixed with clay as the binding agent. Sand procured from river banks is used to shape and mould the desired objects. Because of its softness, it facilitates a balanced final shape and finishing of the products. The soil is red in colour. Precision in policing is important here too, as the use of imperfect soil may lead to breaking of the product when heated. Cow dung is mixed with the river soil as it allows the wax to melt out of the cast and helps prevent it from getting stuck on to the soil.

Two different types of wax are used, both of which serve the same purpose. The first type is bee wax, which is extracted from the bee hives available in the forest, while the second type is candle wax. Since candle wax breaks easily, it is mixed with picchu (coal tar) and firewood. Charcoal is used to prepare a mixture for covering the layers on the model.

I have been acquainted with dhokra objects for at least last 15 years at Bhubaneswar’s Ekamra Haat, Utkalika showroom, Tribal museums and many fairs and exhibitions, but had never got chance to meet Dhokra artisans in their own settings.

Some exclusive Kondh Dhokra sculptures exhibit at Bhubaneswar’s Tribal Museum

This year in February on my way to Niyamgiri, the abode of Dongra Kondhs I chanced upon to visit two Dhokra villages, Jagdalpur and Jhingidi in Rayagada district.

Jagdalpur, a tiny village in the deep interior about 5 km from the highway that connects Odisha’s Gopalpur Port with Raipur, capital of Chhattisgarh across Vedanta’s Alumina Refinery is inhabited by Desia Kondhs, a branch of Kondh that has shifted to agriculture mode. The other two are Dongoria and Kutia Kondhs, comparatively primitive.

Also, Read Here:

Dongria Kondhs of Nimayagiri – Mother Nature’s Own Children

For Desia Kondhs dhokra is very significant in their social and cultural life. Though they don’t make themselves the shining black coloured dhokras made at Jagdalpur and Jhingidi by the dhokra community are a treat to eyes. Traditionally the objects are made for Kondhs to meet their religious beliefs and social and cultural life.

The Kondhs worship dhokra items of different animals and ritual objects that represent the well-being, prosperity and wealth, good and successful hunting. For example to increase wealth Kondhs worship buffaloes and snakes in case of multiple deaths due to snakebite in the family. Deer are worshipped to increase their family size.

Some exclusive dokra objects in the collection of ODIART Purvasha Museum in Chilika

Kondhs also worship various forms of Dhokra to show respect to their ancestors and to get protection from malevolent magic, ghosts and spirit. Kondhs display and worship these dhokras during various religious festivals and social occasions, such as Meriah Parab and Nua Khai.

Dhokra objects are also a symbol of status for Kondhs. They give a large quantity of dhokra items to their daughters. The gift items fall into two categories, linga and darb. While the former is meant for worship, the latter boasts the economic status of the girl’s family. Mostly the dhokras used in marriage consists of elephants, horse, Kondh men and women.

Today, however, there has been a major shift in dhokra items produced in these two villages. As dhokra has become major showcase objects across urban homes, the artisans with the help of NGOs and self-help groups have started creating eye-catchy items and toys for children.

The next visit of mine was to Sadeibareni near the picturesque Saptasajya Hills in Dhenkanal District. A village of hundred artisan families, Sadeibareni offers a view straight from the Copper Age setting. Once a nomadic community setting up makeshift camps at villages near and far selling ritual objects to rural households the community is now settled at Sadeibareni for last three decades. What makes Sadehiberani dhokras unique are the blue tone in contrast to the black colour of Rayagada dhokras.

I met Kastur Majhi, a leading artisan of the village who showed us the kiln and explained how smelting is done and how it was carried out earlier. The head relived in the front wall of the kiln is their favoured deity Kalika resembling a monster face. They worship him before the smelting process and abstain from worldly activities during the month of Chaitra (Jan-February). A stroll through the village will let you explore different stages of dhokra making and the role of people associated with the craft.

Earlier they would make mana jagara (lamp stands) for rural households which are used during the holy Kartika and Margasira months. They would walk down in groups from village to village and supply these objects and in return would get in kind – clothes, groceries, and other daily need items. Today they are settled and make objects of contemporary need and supply to agencies based in Bhubaneswar.

After spending two hours I returned to Bhubaneswar with a happy feeling – one of India’s greatest contribution to the world of ancient technology is still rooted in its old world charm and form.

Author Jitu Mishra

Pictures – Jitu Mishra and Mahaprasad Nanda

Jitu can be contacted at jitumisra@gmail.com