Raja Srikar Bhanja of Ghumsar! History might have forgotten him, but his contribution to art and culture even today stuns visitors and art scholars alike.

A distant relative of Kabi Samrat Upendra Bhanja, Srikar came to rule in 1790. However, after ruling 9 years in 1799 he renounced to lead the life of an ascetic devotee of Lord Sri Rama in South India. In 1819, the British unseated his son and successor Sri Dhanajaya Bhanja and reinstalled him again as the king of Ghumsar (today’s Bhanjanagar). While being in the heartlands of Southern India Srikar had got exposed to a diverse range of mural heritage in different courts including the Maratha wooden buildings.

Once started a fresh reign, Srikara took initiatives to experiment with his yearning for his beloved Ghumsar. A major project was the construction of a wooden and stone temple for Lord Biranchi Narayan taken from his capital to Buguda, 25 km away and the project site. The building was painted by murals said to be so fine that they looked as if the divine artisan Viswakarma himself has made them. The year of its construction was 1820.

Travel Tips

Biranchi Narayan Temple is widely celebrated as the Wooden Konark of Odisha. A legend goes: Once a cowherd boy while tending cattle stuck his feet against a metal plate at the foothill. Consequently, the villagers dug up the portion and unearthed the life-size image of Biranchi Narayan.

The temple is built in the form of a chariot driven by seven horses. Apart from murals, the temple is noted for its remarkable wood carvings on the ceilings of the mandapa and the jambs of the entrance door.

Buguda is surrounded by a number of other interesting spots of tourist interest, the most noted being Buddhakhol, 3 km away. Amidst forests and streams, there is a cluster of 5 Hindu temples at the top of the hill, dedicated to Lord Shiva. In the past, the area was part of a major Buddhist civilisation which can be testified with the findings of a number of Buddhist images and caves where Buddhist monks once lived to meditate during rainy seasons.

Buguda can be approached from Berhampur (70 km), South Odisha’s largest city, Gopalpur – on –Sea (75 km) and NH-16 at Khalikote (70 km). A ride to Buguda from these cities/towns is going to be an experience of a lifetime, especially if you are travelling in monsoon and winter. On your way, you would discover rich ethnic life of Southern Odisha along with lush green paddy fields, hills and unspoiled forest.

Buguda does not have staying options. However, in Berhampur and Gopalpur one may find a number of hotels/resorts of various ranges. We recommend avoiding Berhampur which is highly chaotic and messy. Gopalpur – on – Sea is a better option where one can easily spend two days relaxing in one of the finest beaches on the Bay of Bengal.

In Odisha, Puri was the major centre for Odishan chitrakaras, whose work was connected with the Jagannath Temple.

Depiction of Schematic Map of Puri Srikshetra in Biranchi Narayan Temple

Also, Read Here:

Monks, Monasteries and Murals – A Photo Story on Puri’s Two Legendary Mathas

Some of them moved to various sassana (Brahmin villages) villages around Puri to work for their Brahmin patrons. The widely celebrated Raghurajpur and Dandashahi villages are attached to two sassanas near Puri.

Also, Read Here:

Raghurajpur – An Open Air Museum

During the 18th century, secondary Jagannath temples were built in feudatory (gadajat) states of Odisha. Chitrakaras were sent out to provide replacement images and perform other services to temples. As a result of these migrations, several distinctive styles of paintings evolved, including Dakshini style of Ganjam.

Also, Read Here:

Travel through Digapahandi – Ganjifa’s Last Bastion

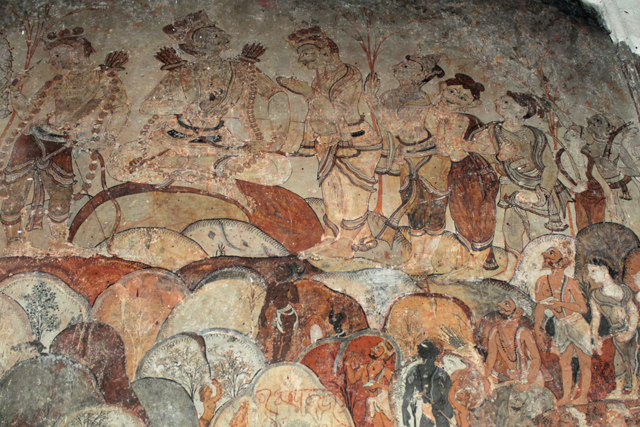

Some of these chitrakaras had settled at nearby villages, such as Mathura and Balipadara. Today both villages are active centres of art and craft. According to local people, chitrakaras from either of these two villages had painted the murals of Biranchi Narayan Temple where more than half of the repertoire represents Ramayana Katha. Today their conditions have deteriorated to a large extent. However, the remnants still shine thanks to the burnished surface of the wall over which the murals are drawn.

Painted according to classical canons, the Buguda murals have an exceptional aspect, the subdued earthy palate. In addition to yellow and russet ochre (appear in older pattachitras of Puri) a greyish green is prominent. Blue occurs very rarely and in a duller form then the pattachitras. Another unusual feature is the unusual amount of white background in the narrative panels. This was perhaps to make simply the story clear. Another feature of the panel is that they are not executed in sequential order and appear like a jigsaw puzzle. The first three sections of wall organized in neat registers and balanced as a whole with repeated elements of design, but all later panels move in haphazard manners, at times from right to left, at times from left to right and at times from top to bottom. It is believed that the irregularity meant for depicting varieties and for not making the overall organizations too predictable and monotonous.

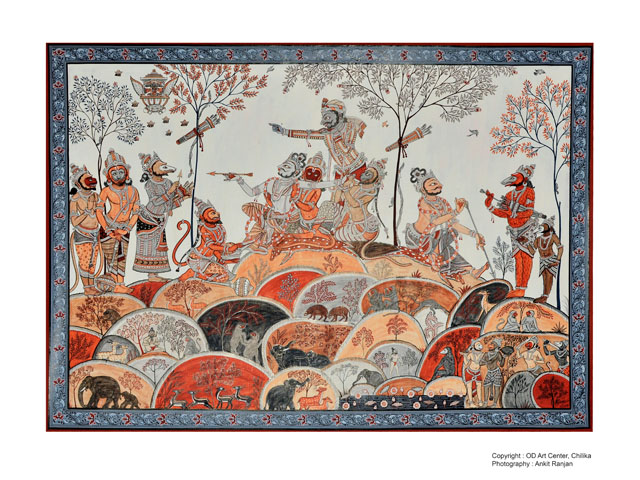

Four major images of the rear of the temple abandon the sequence of each episode. Each panel presents a single event drawn from the Vana Parva (forest section) of the Ramayana, following Rama’s exile. In each, the principals are seated on top of a hill, which is filled with rural details. Most heads are tilted upward, providing a deliberate and heroic cast to their actions. The occasionally drawn down turned positions suggest pensiveness, modesty or subservience. Characters are further simplified with a single curve defining the leg muscle and knee joint, or the leonine male torsos, their shoulders turned almost frontally.

Depicting landscape is a major feature of Buguda paintings. Hills in the four iconic panels are defined by overlapping lobes, their edges outlined in contrasting hue and edges with curved cross-hatching primarily to suggest volume. These multi-coloured lobes are cunningly populated with varied plants and creatures including monkeys and bears.

The pattern used for landscape depiction is also carried by noted pattachitra artist Bijay Parida about whom we have done two stories earlier. One of his creations depicting the Vana Parba episode is highly influenced by Buguda murals. It is exhibited at ODIART Purvasha Museum.

Also, Read Here:

Celebrating Seasons in Patachitra – a Tribute to an Artist’s Dream and Passion

The murals of Buguda is the first major attempt of professional paintings in Odisha’s pictorial tradition and till today play as a role model for a host of pattachitra artists including Bijaya Parida. The Buguda artists had devised their own forms with a sense of innovation and experiment in which narrative concerns were part of the picture.

Author: Jitu Mishra

He can be contacted at jitumisra@gmail.com